Key Takeaways

- The final superconducting magnet built in the U.S. for the high-luminosity upgrade to the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) has left Berkeley Lab on its way to CERN for the first stage of its journey.

- These so-called quadrupole magnets, which focus the particle beams, will, for the first time, use superconducting niobium-tin cables to produce stronger magnetic fields, resulting in more tightly focused beams and higher collision rates in the LHC, thereby improving experiments and broadening research opportunities.

- Multiple national laboratories collaborated to design and build these advanced magnets, with a team from Berkeley Lab winding the superconducting wire into cables and then assembling the coiled cables into the quadrupole magnets.

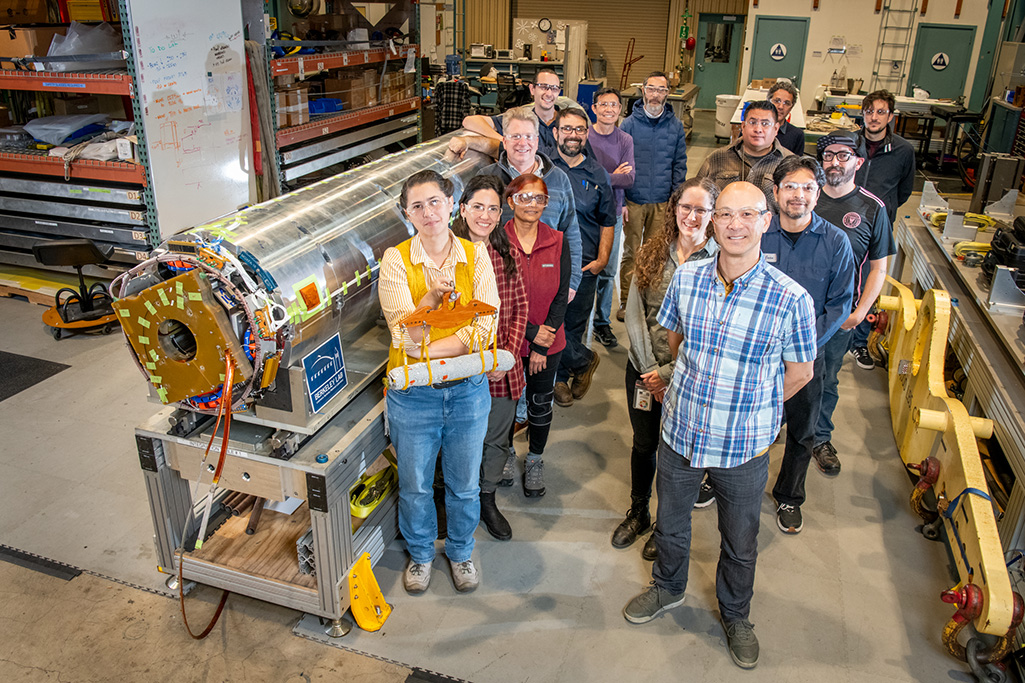

The last of 21 new superconducting quadrupole magnets for the High-Luminosity Large Hadron Collider Accelerator Upgrade Project, or HL-LHC AUP, has left the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) for testing before shipment to CERN in Switzerland for installation in the LHC, the world’s most powerful particle collider.

These advanced magnets use niobium-tin (Nb3Sn) superconducting cables to generate magnetic fields much higher than those of existing magnets. It will be the first time such magnets are used in a particle accelerator, enhancing the LHC’s capabilities to advance fundamental research and enable new discoveries in high-energy physics and related fields.

The magnets are the result of over twenty years of dedicated R&D in Nb3Sn technology and reflect the combined efforts of scientists, engineers, technicians, and operations staff from CERN and four U.S. national laboratories: Berkeley Lab, Brookhaven National Laboratory (Brookhaven Lab), Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), and the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory at Florida State University.

“This outstanding achievement is a testament to the hard work and successful collaboration between experts from across the DOE’s national laboratory complex and CERN,” says Cameron Geddes, director of the Accelerator Technology & Applied Physics (ATAP) Division at Berkeley Lab. “These powerful new magnets promise to boost the LHC’s capabilities and open new avenues for scientific research and exploration.”

A successful multi-lab collaboration

This more than 20-year, multi-lab development of Nb3Sn-based superconducting magnets has transformed precision in accelerator engineering by pushing the boundaries of materials science, microscopic tolerance control, and advanced diagnostic testing. Initially starting as a dedicated R&D project in 2003, this work evolved from creating subscale models only 30 cm long to designing magnets more than 60 cm in diameter and 4.5 meters long.

The Berkeley Lab Center for Magnet Technology—a team from ATAP and the Lab’s Engineering Divisions that serves as a center of expertise in magnetic systems science and engineering—played a key role in building these new magnets by converting Nb3Sn superconducting wires into cables. Teams from Fermilab and Brookhaven Lab then turned these cables into magnet coils and sent them back to Berkeley Lab for assembly into quadrupole magnets.

After room-temperature testing at Berkeley Lab, the magnets were sent to Brookhaven Lab for vertical testing and performance evaluation at cryogenic temperatures. Once testing was successful, they were transported to Fermilab for installation into a cryo-assembly that houses two magnets within a stainless steel vessel called the Cold Mass. The magnets were then retested before being shipped to CERN for installation near the ATLAS and CMS detectors in the LHC’s interaction region.

“One of the things we can be proud of is the ‘machinery’ that was put in place to execute the project using unique and critical capabilities in our labs,” says Giorgio Apollinari, project director for the HL-LHC-AUP at Fermilab.

According to Apollinari, a multi-lab collaboration of this complexity faces “three main challenges: communication, communication, and communication.”

“Openness and transparency are what make highly advanced technical activities successful, because when problems surface (and they will), the team is the first, and very often, the only line of defense to address and solve them. There is no ‘outside consultant’ who can wave a magic wand to solve technical problems.”

Over the course of twenty years, the team faced several significant technical challenges in developing these new magnets. These included issues from structural fractures to microscopic tolerance issues. For instance, engineers working on the magnets found that the difference between a successful magnet and a failure was a tolerance limit of just 50 microns—thinner than a strand of human hair.

For example, in four magnets that failed acceptance testing, the coils were manufactured slightly smaller at the ends of the magnet, explains Daniel Cheng, a mechanical engineer in Berkeley Lab’s Engineering Division and the deputy control account manager for magnet assembly. “This resulted in insufficient compression, allowing the coils to stretch and move when powered up to its nominal operating current of more than 16,000 amps.”

This movement, says Cheng, generated frictional heat, causing the magnet to quench—a sudden, unpredictable loss of superconductivity due to localized heating that can cause irreversible damage to the magnet. Sections of these coils were imaged at CERN using a high-resolution 3D CT scan, which revealed the “smoking gun”: broken strands and filaments in the cables. To address the problem, the team applied higher compression margins to ensure they did not suffer insufficient compression due to the small 50-micron tolerance.

Another challenge arose when a major failure occurred during testing of a second magnet prototype: an aluminum shell surrounding the magnet broke under stress because a sharp corner cut into it, and, along with certain heat treatments, this made the material prone to microcracks.

Cheng says the problem was solved by reverting to an earlier heat treatment and by improving the design to better manage stress concentrations. This modified approach prevented the production magnets from experiencing the same problems. Applying stringent engineering quality assurance procedures and controls during assembly and repair was critical to producing these challenging, cutting-edge magnets.

“Despite these and other challenges, the project maintained a healthy collaboration that avoided blame and focused on problem-solving,” he says.

“Most people unfamiliar with how national labs work might assume a somewhat undisciplined, purely scientific environment,” says Michael Anerella, interim director of the Superconducting Magnet Division at Brookhaven Lab, who led the lab’s contributions to the HL-LHC AUP. “It is important to recognize that it is a formal DOE Project, and as such, is judged by, and conformed to, strict cost and schedule constraints.”

In particular, adds Anerella, the project schedule, developed in close coordination with CERN, was carefully managed. “This is not an easy accomplishment in a project in which work and dependencies were distributed across several laboratories; it therefore requires discipline similar to that in industry.”

By the end of more than two decades of research and development, the HL-LHC AUP successfully transitioned Nb3Sn technology from a research concept to a reliable engineering standard, culminating in the delivery of 21 next-generation superconducting magnets to CERN.

A path to new physics

These magnets will serve as the final focusing magnets for the particle beams produced by the LHC and will be installed in the LHC’s accelerator tunnel, where the beams collide. They can generate magnetic fields up to 12 T—significantly higher than the 8 to 9 T produced by niobium-titanium magnets currently used in the LHC—to create more focused particle beams with much higher luminosity than the existing beams.

“They will be critical to increasing the luminosity of the LHC by an order of magnitude,” says Dimitri Denisov, deputy associate laboratory director for high-energy physics at BNL, who began working on the project in 2019. “This will provide scientists with access to rare processes that the LHC can’t currently study.”

Luminosity is a key measurement of the LHC’s performance because it directly correlates with the number of collisions at the accelerator’s interaction point over a given time. Higher luminosity enables experiments to collect more data, allowing them to observe rare or unexpected processes.

“The additional ‘squeezing’ of the beam by the more powerful magnets will increase the number of collisions delivered to experiments at the LHC,” says Apollinari,” allowing continued studies of the Higgs mechanism and observation of rare phenomena that could reveal themselves after 2030 when the upgraded LHC will start operating.”

The Higgs boson, first detected by the LHC in 2012, is the second heaviest known particle. It was the only fundamental particle predicted by the Standard Model that experiments had not observed before the LHC became operational. The Higgs boson is essential for understanding the origin of mass in the universe. As noted in the 2023 Particle Physics Project Prioritization Panel (P5) report, which outlines particle physicists’ recommendations for the next decade, the high-luminosity upgrade will address “key questions about the Higgs boson while searching for new particles and phenomena.” The increase in collisions may also offer valuable insights into other fundamental scientific questions about dark matter and dark energy.

“This project is a testament to the long vision and commitment of DOE Office of High-Energy Physics (OHEP) to invest in accelerator technology that enables new physics,” says Soren Prestemon, head of ATAP’s Superconducting Magnet Program and serving as Berkeley Lab’s representative to the HL-LHC AUP. The new magnet technology that enabled the HL-LHC AUP exemplifies the impact of magnet R&D. Prestermon also directs the U.S. Magnet Development Program, a national initiative funded by OHEP and led by ATAP to advance magnet technology for future colliders.

The teams at U.S. national labs wish to thank CERN for its invaluable support in enabling a successful project.

The Department of Energy’s Office of Science, Office of High Energy Physics funds the DOE 413.3B project and the research presented here.

To learn more…

Major Milestone in Large Hadron Collider Upgrade

New Magnets for Large Hadron Collider Upgrade Successfully Pass Halfway Mark

National Academies Publish High-Field Magnets Study

Superconducting Magnets: Enhancing The Capabilities of Particle Accelerators

Building Superconducting Magnets for CERN’s LHC Upgrade

For more information on ATAP News articles, contact caw@lbl.gov